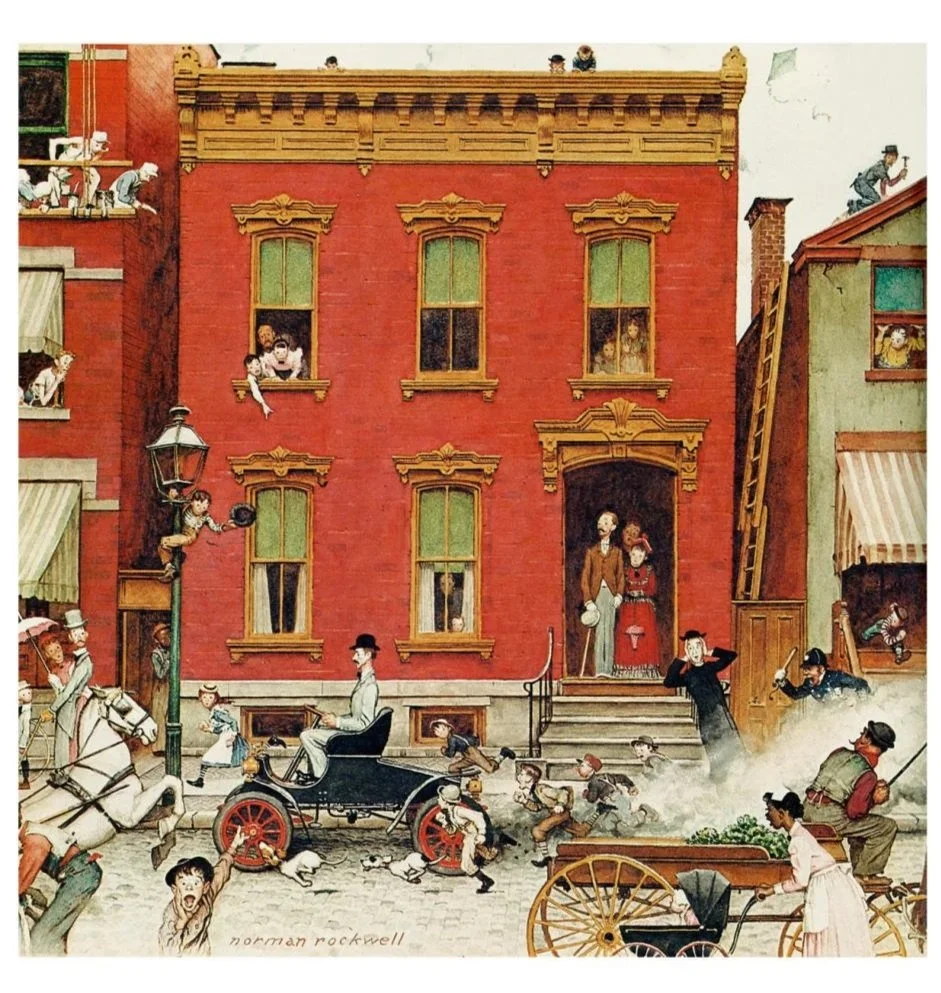

The street was never the same again

The street was never the same again. Norman Rockwell, 1953

Without thinking too much about it in specific terms, I was showing the America I knew and observed to others who might not have noticed.

This is how Norman Rockwell summed up his career as one of the most important and recognized illustrators of mid-20th-century America. Born in New York in 1894, he entered the School of Arts at just 14 years old, and at 16 he enrolled in the School of Design. Shortly after, still a teenager, he was appointed art director of Boys’ Life, the magazine of the Boy Scouts of America, with which he would collaborate for six decades.

Thus began his early career as an illustrator for numerous American publications, which would lead him to create more than 300 covers for the well-known magazine The Saturday Evening Post, producing the first one in 1916, at the age of 22. He even designed some covers for the famous magazine Life in its early issues.

Until his death in November 1978, Rockwell was a very active artist, producing more than 4,000 works in which he caricatured the America of his time. As a result, the automobile appeared in many of his paintings and illustrations — for example, several Saturday Evening Post covers from the 1920s, where the car is not only the main subject but also serves to emphasize speed.

In the same way, even without showing the entire automobile, Rockwell continued creating covers in the 1930s that conveyed a sense of high speed — for example, the one published on July 13, 1935. That same illustration was later chosen by The Saturday Evening Post for the cover of its November 1976 issue, a special edition about the automobile featuring articles such as America’s Love Affair with the Automobile and The 10 Most Beautiful Cars in History.

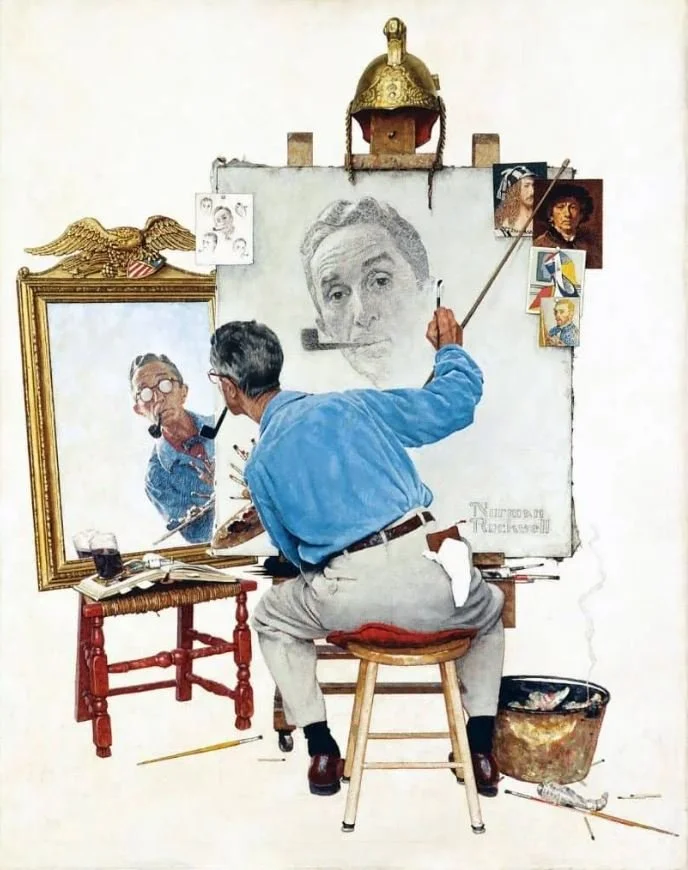

Photography was not only a great source of inspiration for Rockwell but also a working tool in preparing his paintings and illustrations. The artist himself even became the face of the Kodak Retina camera in the 1960s.

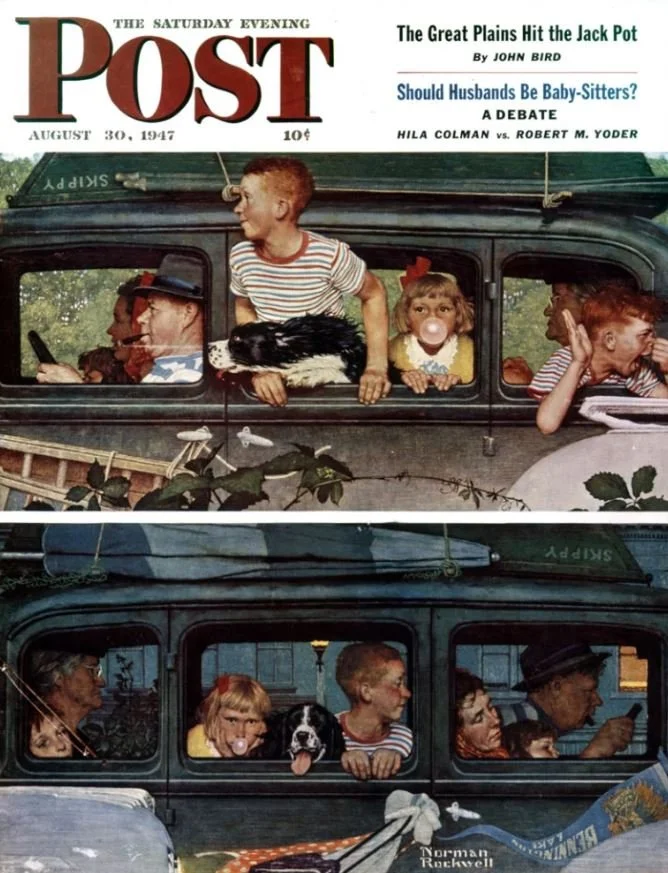

A fine example of this — and particularly relevant in this context — is the cover of The Post from August 30, 1947, titled Going and Coming. In it, a family takes a one-day or weekend summer getaway, probably to a lake in the mountains. In the morning, everyone is cheerful and full of anticipation; by evening, they return practically exhausted. Two scenes aboard the same car — a 1931 Dodge — over the course of a few hours. The automobile becomes an essential tool for enjoying family leisure time.

Studies for Going and Coming

Saturday Evening Post cover, August 30th 1947

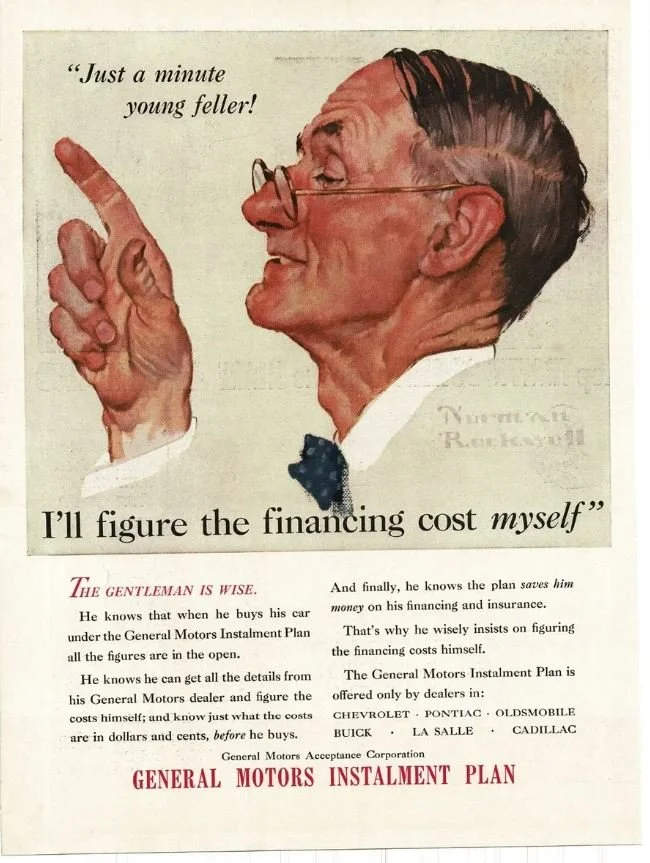

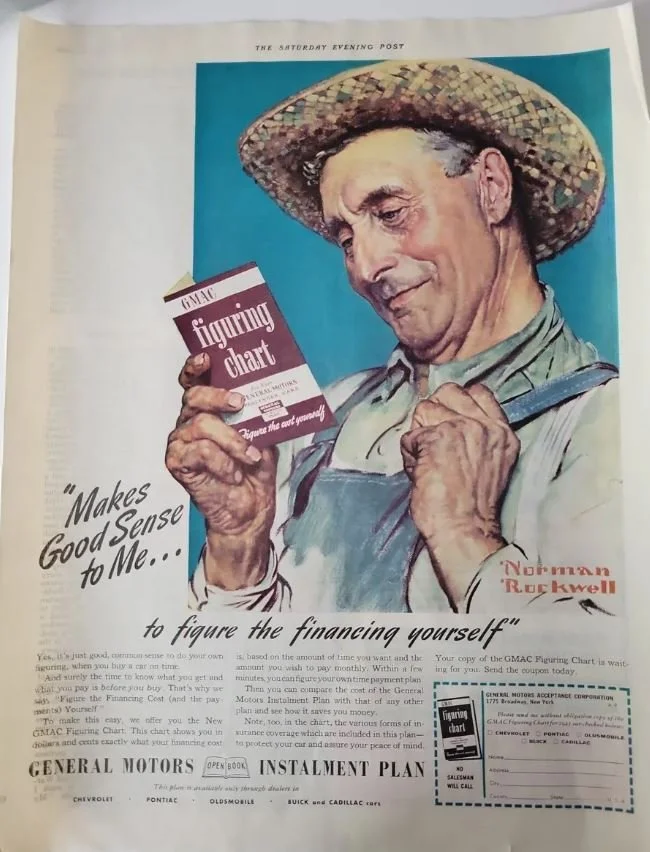

Rockwell also became, almost unintentionally, a well-known advertising illustrator, creating artwork for many famous brands such as Coca-Cola and General Electric, among many others — and even for the automotive industry, including notable work for Ford, Plymouth, and General Motors.

For the latter, between 1939 and 1940, he produced several illustrations to promote GM’s own financing plan, which aimed to encourage car purchases in the United States.

In these advertisements, it is quite curious that no Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Chevrolet, Buick, LaSalle, or Cadillac appears. Instead, Rockwell depicted the average American worker — shown either reviewing different financing options or holding a booklet in his hands. This booklet could be requested from GM and would be mailed to customers, allowing them to estimate financing costs based on their desired payment amount or number of installments. As usual, these works are characterized by Rockwell’s distinctive, caricature-like style.

From the late 1940s through part of the 1950s, Rockwell created several illustrations that Plymouth used to advertise its new models. Once again, the cars themselves did not appear in the images — reminiscent of the old Duesenberg ads from the mid-1930s.

Instead, he depicted heartwarming family scenes in which the car is mentioned — often as something that especially excites the children — emphasizing the family-oriented nature or even the image of the “perfect family” that Plymouth wanted to promote.

These works also fit perfectly within the broader scope of Rockwell’s art, which throughout his life sought to represent the “American Dream,” encompassing countless everyday moments and especially scenes of the American working class. His works depicting various professions are particularly well known.

With scenes such as Merry Christmas, Grandma! We came in our new Plymouth! or Oh boy! It’s Pop with a new Plymouth! the brand advertised its cars without even showing them.

One of the first advertisements, however, did show part of the 1947 Plymouth being promoted — though only in the background. Once again, the scene depicted a slice of American culture: a family arriving at the grandparents’ house for dinner. As the grandmother takes the turkey out of the oven, the grandfather remarks, “Here they come, Mom! And Jim won´t need the wish-bone — they´ve got their Plymouth.”

In the early 1950s, in a letter dated May 15, 1951, Henry Ford II reached out to Norman Rockwell to arrange a meeting that would lead to what was probably Rockwell’s most interesting collaboration with the automobile industry. Ford commissioned him to create the 1953 calendar to commemorate the company’s 50th anniversary.

The result was seven illustrations, the first of which features the three generations of the Ford family — Henry, Edsel, and Henry II — on the cover. The remaining six illustrate the calendar’s monthly pages, two per spread.

The Boy Who Put the World on Wheels. Norman Rockwell, 1953

January and February feature a young Henry Ford in his bedroom, where he repaired clocks for his neighbors. In the illustration, The Boy Who Put the World on Wheels, he appears deep in conversation with his father, proudly showing him the inner workings of a wall clock.

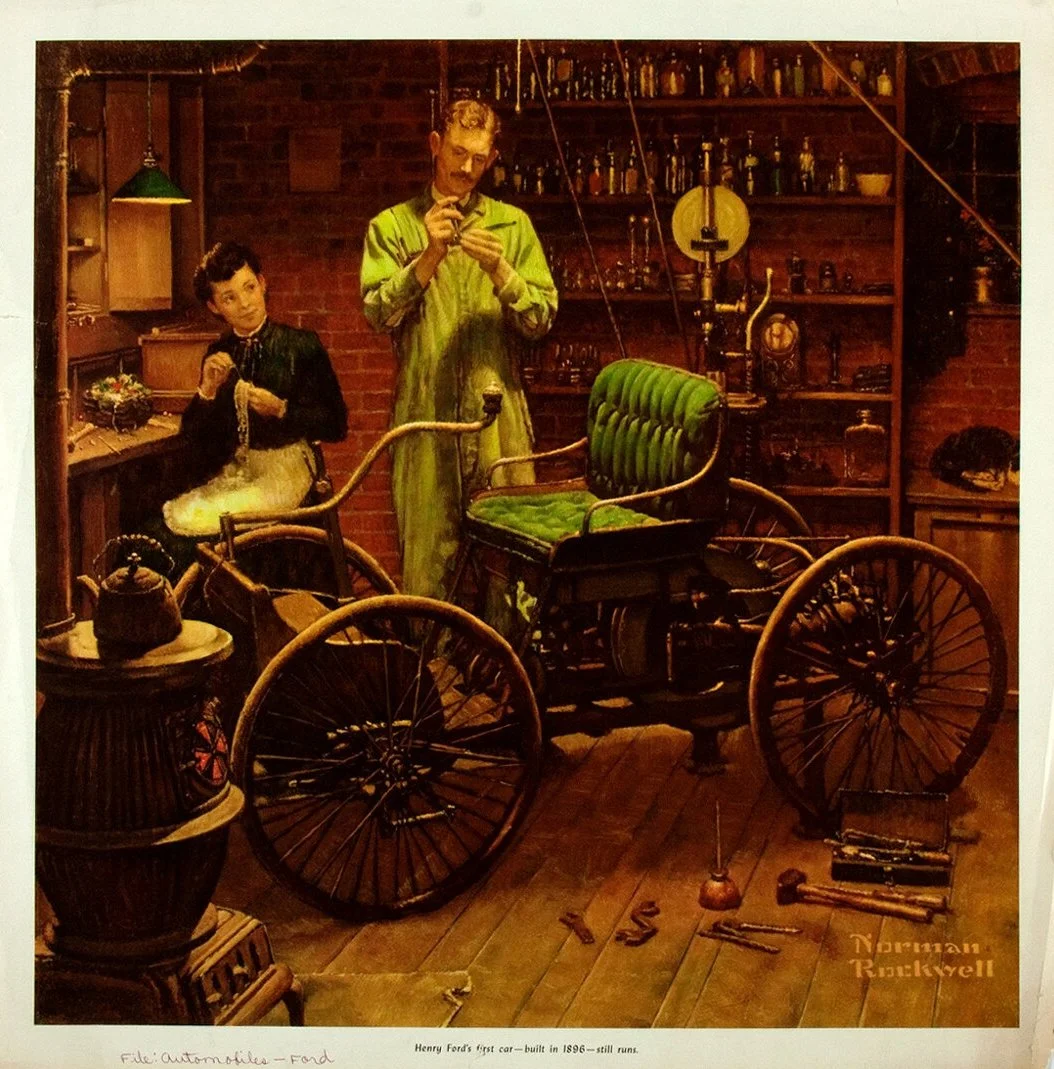

March and April depict a slightly older Henry Ford — now a young man — working alongside his wife in the garage of their home in 1896, where he built his very first prototype. The image captures the humble beginnings of an inventor who would soon revolutionize transportation.

Henry Ford´s first car. Norman Rockwell, 1953

May and June present the most iconic illustration of all, both for its title and its historical significance: “The Street Was Never the Same Again.” Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post on March 28, 1953, the lively scene shows a caricatured Detroit street transformed by the arrival of a 1903 Ford Model A speeding past. Onlookers react with astonishment — adults alarmed, children chasing after the car, curious workers pausing their tasks, frightened horses rearing, and even a bewildered policeman unsure what to do — all capturing the moment when the world first felt the impact of the automobile.

The street was never the same again. Norman Rockwell, 1953

July and August celebrate the Ford T, described in the accompanying text as, swifter than a hare and more enduring than a mule. Set in a rural landscape, the illustration highlights the car’s popularity among farmers and doctors, thanks to its all-terrain reliability—perfect for the rough, unpaved roads of the era. The caption proudly notes that thirty-six million Fords had rolled off the assembly line in just fifty years.

Boss of the road, the car that brings you back. Norman Rockwell, 1953

September and October introduce a more contemporary scene, reflecting how the automobile had become part of leisure and recreation for people of all social classes. It also acknowledges the vast reach of the American highway system, which by 1953 extended more than 3.2 million miles across the country. Finally, November and December depict Henry Ford II, who had served as president of the company since 1945, symbolizing the continuation of his grandfather’s vision into a new generation.

During the creation of the calendar, Rockwell also designed the Christmas card that Ford would use to wish everyone a Merry Christmas at the end of 1951. The card foreshadowed the company’s upcoming collaboration with the artist in celebration of its 50th anniversary. The scene depicts a family riding in a horse-drawn sleigh crossing paths with another speeding by in a Ford T in the opposite direction.

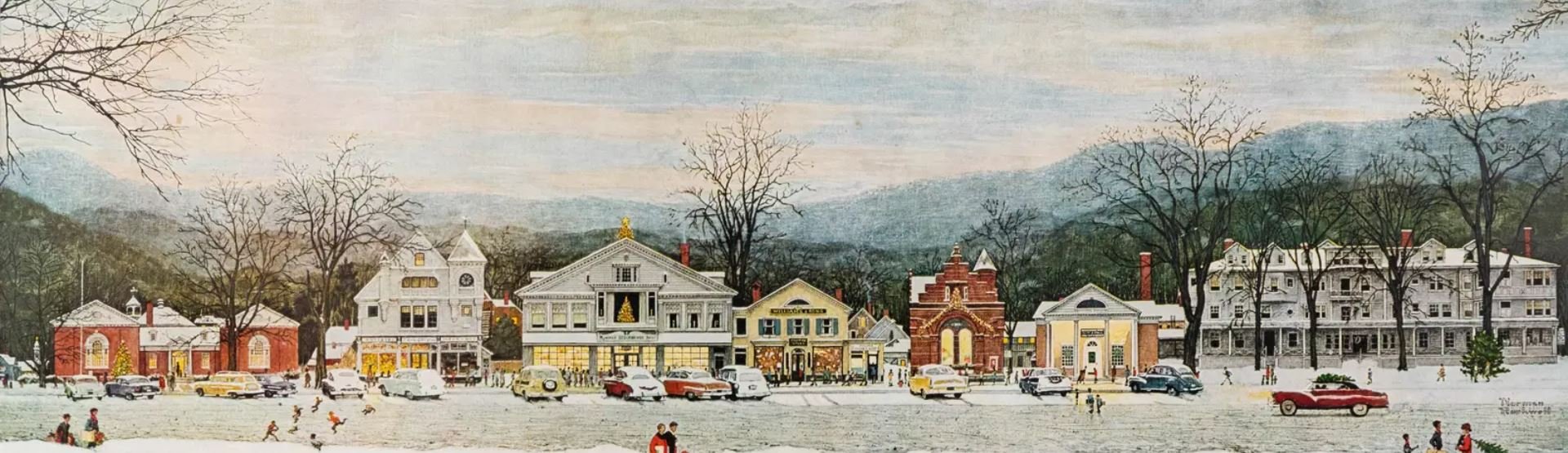

This brief article offers only a glimpse into the many works of Norman Rockwell in which the automobile takes center stage. Among his more than 4,000 creations, there are many other scenes of this kind, as it was not possible to exclude the automobile when representing daily life in America during his time. From the early years of motoring, such as the 1917 scene depicting a car surrounded by children and stuck in the snow outside a gas station, to later decades in the forties, fifties, and sixties, with works like Fixing a Flat, Breaking Home Ties, or Stockbridge Main Street at Christmas.

Stockbridge main street at Christmas. Norman Rockwell, 1967

References:

nmr.org

thehenryford.org